Several months ago, as The New York Review of Books was preparing to publish its review of Power Wars, I received a letter from its editor, Robert Silvers, asking whether I would like to write a review essay about Playing to the Edge by Michael Hayden, the former head of the NSA and the CIA. I accepted the assignment. The essay I wrote weighs Hayden’s book and his broader contribution to the public debate over post-9/11 issues like warrantless surveillance, torture, and targeted killings against the standard he sets for the role an intelligence officer should play in a modern democracy. The paywall link is down and it may be read for free here.

Carter and Dunford grovel a bit re female guards at Gitmo and military commissions independence

Here’s a 4 p.m. before Memorial Day Weekend news dump item. The background is here. (Don’t hold your breath waiting for any similar from Senator Ayotte though!)

Statement by Secretary of Defense Ash Carter and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph F. Dunford Jr. on Gender-Neutral Staffing of Guard Forces at JTF-GTMO

Military commissions are part of our system of military justice. The Department of Defense, and we personally, are committed to fairness and transparency in military commission proceedings, and to the independence of the judges who oversee them.

Our comments and those made by other senior officials regarding gender-neutral staffing of guard forces at JTF-GTMO have given rise to a concern that the comments may have appeared to be intended to influence the proceedings. We continue to believe that our military has legitimate and strong interests in gender-neutral staffing, integration of women into all positions, and the prevention of gender discrimination. We also believe that protection of the freedom of religion, and the access to representation, are fundamental to who we are. To be clear, we had no intention to influence the military judges presiding over the military commissions. Along with other senior officials in the Department, we respect the role of military judges in evaluating these issues as they might affect an individual case and we fully expect them to make their independent determinations on these and other matters.

Ted Cruz and Senate GOP want to expand the Gitmo transfer ban — including to Afghanistan and Israel, but exempting Saudi Arabia

The newly unveiled Senate Armed Services Committee version of the National Defense Authorization Act has a provision that would wildly expand the number of countries to which the U.S. government may not transfer low-level Guantanamo detainees. Specifically, it would ban transfers to any nation for which the State Department has issued a travel warning. Senator Ted Cruz, Republican of Texas, has taken credit for adding it to the bill during the committee’s closed-door markup last week. This provision is not in the House version of the NDAA, so it has the feeling of something that will likely get removed in conference. But it’s interesting to consider.

First, context: Current law already bans the transfer of detainees to countries that are deemed by the State Department to be state sponsors of terrorism. Those are: Iran, Sudan, and Syria. Current law also already bars the transfer of detainees to countries whose government lacks the capacity to keep an eye on them, which is why the low-level Yemeni detainees are all getting resettled in other countries. UPDATE: And current law already specifically bans transfers to Libya, Somalia, Syria (redundantly) and Yemen.*

Cruz’s provision in the Senate version of the NDAA would go further by banning the transfer of any detainees to countries where the State Department has issued security-related travel warnings to Americans, except for Saudi Arabia. That list is much, much longer: Afghanistan, Algeria, Burkina-Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Colombia, Congo, El Salvador, Eritrea, Haiti, Honduras, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Kenya, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Mexico, Niger, Nigeria, North Korea, Pakistan, Philippines, South Sudan, Saudi Arabia [however, as noted, it is exempted], Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, Venezuela, and Yemen.

Comparing that list to the list of the 80 remaining detainees, we see that the most important change this would make would be barring repatriations to Afghanistan. There are two three [Update: new PRB recategorization disclosed today for Obaydullah, whose case I wrote about in this 2012 article] detainees on the list of those recommended for transfer who are Afghans, along with six five other Afghans who are not currently recommended for transfer but someday may be if the parole-like Periodic Review Board decides that it is no longer necessary to keep holding onto them.

Eight other detainees could also, in theory, be affected by this: on the transfer list, a Tunisian, and, on the not currently recommended for transfer list, two Algerians, a Mauritanian, three Pakistanis, and a Palestinian.

Query: By what logic did Cruz decide to exempt Saudi Arabia but not Israel? I’m not sure, but note that as a general matter, the provision explains that it is the “It is the sense of the Senate that countries that pose such a significant travel threat to United States citizens that the Department of State feels obliged to issue a travel warning should not be considered an appropriate recipient of any detainee transferred from United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; and if a country is subject to a Department of State travel warning, it is highly unlikely that the government of the country can provide the United States Government appropriate security and assurances regarding the prevention of the recidivism of any detainee so transferred.”

Most of both lists are made up of detainees from countries that are already effectively barred from getting repatriations because their home countries are a mess – especially Yemenis. This is not a coincidence, as for years they have stayed behind while other detainees from more stable countries have left under the Bush and Obama administration, even if those leaving were deemed to pose an equal or greater risk as individuals.

Of course, even if this were to stay in the NDAA, by the time it becomes law there will likely be significantly fewer detainees at Guantanamo. The Obama administration has said it expects to get most or all of the remaining 27 28 detainees on the transfer list out by by the summer – if Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter signs off on the deals the interagency has approved, at least. As of last count, there were already 14 such deals ready to go, so we might see more than a dozen transfers in June if he notifies Congress that he has moved on them, setting off the 30-day waiting period.

* International law separately prohibits sending detainees to countries where they are likely to be tortured or persecuted.

Senate Armed Services Committee unveils their NDAA, including detention provisions

One of the undemocratic – or at least, untransparent – things about how Congress shapes American national security law is that the armed services and intelligence oversight committees craft their annual authorization bills behind closed doors, sending them to the floor as a fait accompli. (Another is that these bills contain extensive classified annexes, as Dakota Rudesill, a former ODNI official and national-security congressional staffer who is now at Ohio State wrote in a recent academic paper, “Coming to terms with Secret Law,” summarized in this Lawfare post yesterday.)

The Senate Armed Services Committee has now finally unveiled the version of the National Defense Authorization Act for 2017 that it marked up last week. (The House passed its version earlier this week; after the full Senate passes its version, it will go to conference.) Here are the Guantanamo and Islamic State related provisions in the Senate bill – first the index, then the text.

Index

TITLE X—GENERAL PROVISIONS

Sec. 1021. Extension of prohibition on use of funds for transfer or release of individuals detained at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to the United States.

Sec. 1022. Extension of prohibition on use of funds to construct or modify facilities in the United States to house detainees transferred from United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Sec. 1023. Designing and planning related to construction of certain facilities in the United States.

Sec. 1024. Authority to transfer individuals detained at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to the United States temporarily for emergency or critical medical treatment.

Sec. 1025. Authority for article III judges to take certain actions relating to individuals detained at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Sec. 1026. Extension of prohibition on use of funds for transfer or release to certain countries of individuals detained at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Sec. 1027. Matters on memorandum of understanding between the United States and governments of receiving foreign countries and entities in certifications on transfer of detainees at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Sec. 1028. Limitation on transfer of detainees at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, pending a report on their terrorist actions and affiliations.

Sec. 1029. Prohibition on use of funds for transfer or release of individuals detained at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to countries covered by Department of State travel warnings.

Sec. 1030. Extension of prohibition on use of funds for realignment of forces at or closure of United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

***

TITLE XII—MATTERS RELATING TO FOREIGN NATIONS

Sec. 1221. Extension and modification of authority to provide assistance to the vetted Syrian opposition.

Sec. 1222. Extension of authority to provide assistance to counter the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

Sec. 1223. Extension of authority to support operations and activities of the Office of Security Cooperation in Iraq.

***

Text

Subtitle D—Counterterrorism

SEC. 1021. EXTENSION OF PROHIBITION ON USE OF FUNDS FOR TRANSFER OR RELEASE OF INDIVIDUALS DETAINED AT UNITED STATES NAVAL STATION, GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA, TO THE UNITED STATES.

Section 1031 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (Public Law 114–92; 129 Stat. 968) is amended by striking “December 31, 2016” and inserting “December 31, 2017”.

SEC. 1022. EXTENSION OF PROHIBITION ON USE OF FUNDS TO CONSTRUCT OR MODIFY FACILITIES IN THE UNITED STATES TO HOUSE DETAINEES TRANSFERRED FROM UNITED STATES NAVAL STATION, GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA.

Section 1032(a) of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (Public Law 114–92; 129 Stat. 968) is amended by striking “December 31, 2016” and inserting “December 31, 2017”.

SEC. 1023. DESIGNING AND PLANNING RELATED TO CONSTRUCTION OF CERTAIN FACILITIES IN THE UNITED STATES.

(a) Designing And Planning Authorized.—Notwithstanding any provision of law limiting the use of funds for the construction or modification of facilities in the United States or its territories or possessions to house individuals detained at Guantanamo, the Secretary of Defense may use amounts authorized to be appropriated or otherwise made available for the Department of Defense for designing and planning related to the construction or modification of such facilities

(b) Individual Detained At Guantanamo Defined.—In this section, the term “individual detained at Guantanamo” means an individual located at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, as of October 1, 2009, who—

(1) is not a national of the United States (as defined in section 101(a)(22) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. 1101(a)(22)) or a member of the Armed Forces of the United States; and

(A) in the custody or under the control of the Department of Defense; or

(B) otherwise detained at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay.

SEC. 1024. AUTHORITY TO TRANSFER INDIVIDUALS DETAINED AT UNITED STATES NAVAL STATION, GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA, TO THE UNITED STATES TEMPORARILY FOR EMERGENCY OR CRITICAL MEDICAL TREATMENT.

(a) Temporary Transfer For Medical Treatment.—Notwithstanding section 1031 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (Public Law 114–92; 129 Stat. 968), or any similar provision of law enacted after September 30, 2015, the Secretary of Defense may, after consultation with the Secretary of Homeland Security, temporarily transfer an individual detained at Guantanamo to a Department of Defense medical facility in the United States for the sole purpose of providing the individual medical treatment if the Secretary of Defense determines that—

(1) the medical treatment of the individual is necessary to prevent death or imminent significant injury or harm to the health of the individual;

(2) the necessary medical treatment is not available to be provided at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, without incurring excessive and unreasonable costs; and

(3) the Department of Defense has provided for appropriate security measures for the custody and control of the individual during any period in which the individual is temporarily in the United States under this section.

(b) Limitation On Exercise Of Authority.—The authority of the Secretary of Defense under subsection (a) may be exercised only by the Secretary of Defense or another official of the Department of Defense at the level of Under Secretary of Defense or higher.

(c) Conditions Of Transfer.—An individual who is temporarily transferred under the authority in subsection (a) shall—

(1) while in the United States, remain in the custody and control of the Secretary of Defense at all times; and

(2) be returned to United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, as soon as feasible after a Department of Defense physician determines, in consultation with the Commander, Joint Task Force-Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, that any necessary follow-up medical care may reasonably be provided the individual at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay.

(d) Status While In United States.—An individual who is temporarily transferred under the authority in subsection (a), while in the United States—

(1) shall be deemed at all times and in all respects to be in the uninterrupted custody of the Secretary of Defense, as though the individual remained physically at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba;

(2) shall not at any time be subject to, and may not apply for or obtain, or be deemed to enjoy, any right, privilege, status, benefit, or eligibility for any benefit under any provision of the immigration laws (as defined in section 101(a)(17) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. 1101(a)(17)), or any other law or regulation;

(3) shall not be permitted to avail himself of any right, privilege, or benefit of any law of the United States beyond those available to individuals detained at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay; and

(4) shall not, as a result of such transfer, have a change in any designation that may have attached to that detainee while detained at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (Public Law 107–40), as determined in accordance with applicable law and regulations.

(e) No Cause Of Action.—Any decision to transfer or not to transfer an individual made under the authority in subsection (a) shall not give rise to any claim or cause of action.

(f) Limitation On Judicial Review.—

(1) LIMITATION.—Except as provided in paragraph (2), no court, justice, or judge shall have jurisdiction to hear or consider any claim or action against the United States or its departments, agencies, officers, employees, or agents arising from or relating to any aspect of the detention, transfer, treatment, or conditions of confinement of an individual transferred under this section.

(2) EXCEPTION FOR HABEAS CORPUS.—The United States District Court for the District of Columbia shall have exclusive jurisdiction to consider an application for writ of habeas corpus seeking release from custody filed by or on behalf of an individual who is in the United States pursuant to a temporary transfer under the authority in subsection (a). Such jurisdiction shall be limited to that required by the Constitution, and relief shall be only as provided in paragraph (3). In such a proceeding the court may not review, halt, or stay the return of the individual who is the object of the application to United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, pursuant to subsection (c).

(3) RELIEF.—A court order in a proceeding covered by paragraph (2)—

(A) may not order the release of the individual within the United States; and

(B) shall be limited to an order of release from custody which, when final, the Secretary of Defense shall implement in accordance with section 1034 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016.

(g) Notification.—Whenever a temporary transfer of an individual detained at Guantanamo is made under the authority of subsection (a), the Secretary of Defense shall notify the Committees on Armed Services of the Senate and the House of Representatives of the transfer not later than five days after the date on which the transfer is made.

(h) Individual Detained At Guantanamo Defined.—In this section, the term “individual detained at Guantanamo” means an individual located at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, as of October 1, 2009, who—

(1) is not a national of the United States (as defined in section 101(a)(22) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. 1101(a)(22)) or a member of the Armed Forces of the United States; and

(A) in the custody or under the control of the Department of Defense; or

(B) otherwise detained at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay.

(i) Applicability.—This section shall apply to an individual temporarily transferred under the authority in subsection (a) regardless of the status of any pending or completed proceeding or detention on the date of the enactment of this Act.

SEC. 1025. AUTHORITY FOR ARTICLE III JUDGES TO TAKE CERTAIN ACTIONS RELATING TO INDIVIDUALS DETAINED AT UNITED STATES NAVAL STATION, GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA.

(a) Use Of Video Teleconferencing.—A judge of a United States District Court shall have jurisdiction to take any of the following actions by video teleconferencing with respect to an individual detained at Guantanamo:

(1) Arraign the individual for a charge under the laws of the United States.

(2) Accept a plea to a charge under the laws of the United States.

(3) Enter a judgment of conviction and sentence the individual for a charge upon which the individual is convicted as a result of such a plea.

An action specified in paragraph (1), (2), or (3) may be taken by video teleconferencing only with the consent of the individual.

(b) Venue.—A judge of a United States District Court may act by video teleconferencing under subsection (a) only where such District Court maintains venue concerning the offense alleged.

(c) Transfer To Serve Sentence Of Imprisonment.—The Attorney General may transfer to a foreign country an offender who is convicted of an offense by reason of a plea entered into as described in subsection (a) and who is under a sentence of imprisonment resulting from such conviction. Any such transfer shall be made for the purpose of the offender serving the sentence imposed on him, and shall be made underchapter 306 of title 18, United States Code, without regard to the provisions of section 4107 and subsections (a) and (b) of section 4100 of that title.

(d) Definitions.—In this section:

(1) The term “individual detained at Guantanamo” means any individual located at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, as of October 1, 2009, who—

(A) is not a national of the United States (as defined in section 101(a)(22) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. 1101(a)(22)) or a member of the Armed Forces of the United States; and

(i) in the custody or under the control of the Department of Defense; or

(ii) otherwise under detention at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay.

(2) The terms “imprisonment”, “offender”, “sentence”, and “transfer” have the meanings given those terms in section 4101 of title 18, United States Code.

SEC. 1026. EXTENSION OF PROHIBITION ON USE OF FUNDS FOR TRANSFER OR RELEASE TO CERTAIN COUNTRIES OF INDIVIDUALS DETAINED AT UNITED STATES NAVAL STATION, GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA.

Section 1033 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (Public Law 114–92; 129 Stat. 968) is amended by striking “December 31, 2016” and inserting “December 31, 2017”.

SEC. 1027. MATTERS ON MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES AND GOVERNMENTS OF RECEIVING FOREIGN COUNTRIES AND ENTITIES IN CERTIFICATIONS ON TRANSFER OF DETAINEES AT UNITED STATES NAVAL STATION, GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA.

Section 1034(b) of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (Public Law 114–92; 129 Stat. 969; 10 U.S.C. 801 note) is amended—

(1) by redesignating paragraphs (4) and (5) as paragraphs (5) and (6), respectively; and

(2) by inserting after paragraph (3) the following new paragraph (4):

“(A) the United States Government, on the one hand, and the government of the foreign country or the recognized leadership of the foreign entity, on the other hand, have entered into a written memorandum of understanding (MOU) regarding the transfer of the individual; and

“(B) the memorandum of understanding—

“(i) has been transmitted to the appropriate committees of Congress, in classified form (if necessary); and

“(ii) includes an assessment, whether in classified or unclassified form, of the capacity, willingness, and past practices (if applicable) of the foreign country or foreign entity, as the case may be, with respect to the matters certified by the Secretary pursuant to paragraphs (2) and (3);”.

SEC. 1028. LIMITATION ON TRANSFER OF DETAINEES AT UNITED STATES NAVAL STATION, GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA, PENDING A REPORT ON THEIR TERRORIST ACTIONS AND AFFILIATIONS.

(a) Limitation.—No amounts authorized to be appropriated or otherwise made available for fiscal year 2017 for the Department of Defense may be used to transfer, release, or assist in the transfer or release to any foreign government or foreign entity of an individual detained at Guantanamo until the Secretary of Defense submits to the appropriate committees of Congress a report on the individual that includes the following:

(1) A description of the individual’s previous terrorist activities.

(2) A description of the individual’s previous memberships in or affiliations or associations with terrorist organizations.

(3) A description of the individual’s support for or participation in attacks against the United States or United States allies.

(b) Form.—Each report under subsection (a) shall be submitted in unclassified form, and may not include a classified annex as a means of conveying any information of material significance to such report.

(c) Construction With Other Prohibitions And Limitations.—The limitation in subsection (a) is in addition to any prohibition or other limitation on the transfer or release of individuals detained at Guantanamo under any other provision of law, including the provisions of subtitle D of title X of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (Public Law 114–92; 129 Stat. 968).

(d) Definitions.—In this section:

(1) The term “appropriate committees of Congress” means—

(A) the Committee on Armed Services, the Committee on Appropriations, and the Select Committee on Intelligence of the Senate; and

(B) the Committee on Armed Services, the Committee on Appropriations, and the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence of the House of Representatives.

(2) The term “individual detained at Guantanamo” means any individual located at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, as of October 1, 2009, who—

(A) is not a citizen of the United States or a member of the Armed Forces of the United States; and

(i) in the custody or under the control of the Department of Defense; or

(ii) otherwise under detention at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

SEC. 1029. PROHIBITION ON USE OF FUNDS FOR TRANSFER OR RELEASE OF INDIVIDUALS DETAINED AT UNITED STATES NAVAL STATION, GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA, TO COUNTRIES COVERED BY DEPARTMENT OF STATE TRAVEL WARNINGS.

(a) Finding.—The Senate makes the following findings:

(1) The Department of State issues travel warnings regarding travel to foreign countries for reasons that include “unstable government, civil war, ongoing intense crime or violence, or frequent terrorist attacks”.

(2) These travel warnings are issued to highlight the “risks of traveling” to particular countries and are left in place until the situation in the country concerned improves.

(b) Sense Of Senate.—It is the sense of the Senate that—

(1) countries that pose such a significant travel threat to United States citizens that the Department of State feels obliged to issue a travel warning should not be considered an appropriate recipient of any detainee transferred from United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; and

(2) if a country is subject to a Department of State travel warning, it is highly unlikely that the government of the country can provide the United States Government appropriate security and assurances regarding the prevention of the recidivism of any detainee so transferred.

(1) IN GENERAL.—Except as provided in paragraphs and (2) and (3), no amounts authorized to be appropriated by this Act or otherwise available for the Department of Defense may be used, during the period beginning on the date of the enactment of this Act and ending on December 31, 2017, to transfer, release, or assist in the transfer or release of any individual detained in the custody or under the control of the Department of Defense at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay to the custody or control of any country subject to a Department of State travel warning at the time the transfer or release would otherwise occur.

(2) EXCEPTION FOR CERTAIN WARNINGS.—Paragraph (1) shall not apply with respect to any country subject to a travel warning described in that paragraph that is issued solely on the basis of one or more of the following:

(A) Medical deficiencies, infectious disease outbreaks, or other health-related concerns.

(B) A natural disaster.

(C) Criminal activity.

(3) EXCEPTION FOR CERTAIN COUNTRY.—Paragraph (1) shall not apply with respect to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

SEC. 1030. EXTENSION OF PROHIBITION ON USE OF FUNDS FOR REALIGNMENT OF FORCES AT OR CLOSURE OF UNITED STATES NAVAL STATION, GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA.

Section 1036(a) of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (Public Law 114–92; 129 Stat. 972) is amended by inserting “or 2017” after “fiscal year 2016”.

***

SEC. 1221. EXTENSION AND MODIFICATION OF AUTHORITY TO PROVIDE ASSISTANCE TO THE VETTED SYRIAN OPPOSITION.

(a) Notice On New Initiatives.—

(1) IN GENERAL.—Subsection (f) of section 1209 of the Carl Levin and Howard P. “Buck” McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015 (Public Law 113–291; 128 Stat. 3541), as amended by section 1225(e) of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (Public Law 114–92; 129 Stat. 1055), is further amended to read as follows:

“(f) Notice To Congress Before Initiation Of New Initiatives.—Not later than 30 days before initiating a new initiative under subsection (a), the Secretary of Defense shall submit to the appropriate congressional committees a notice setting forth the following:

“(1) The initiative to be carried out, including a detailed description of the assistance provided.

“(2) The budget, implementation timeline and anticipated delivery schedule for the assistance to which the initiative relates, the military department responsible for management and the associated program executive office, and the completion date for the initiative.

“(3) The amount, source, and planned expenditure of funds to carry out the initiative.

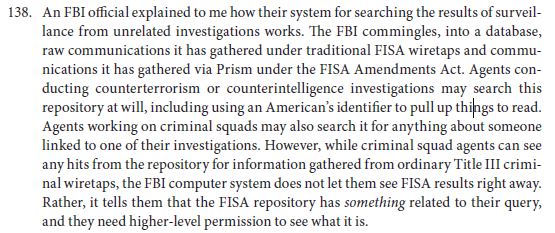

“(4) Any financial or other support for the initiation provided by foreign governments.

“(5) Any other information with respect to the initiative that the Secretary considers appropriate.”.

(2) EFFECTIVE DATE.—The amendment made by paragraph (1) shall take effect on the date of the enactment of this Act, and shall apply with respect to new initiatives initiated under section 1209 of the Carl Levin and Howard P. “Buck” McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015 on or after the date that is 30 days after the date of the enactment of this Act.

(b) Extension Of Authority.—Subsection (a) of such section is amended by striking “December 31, 2016” and inserting “December 31, 2019”.

SEC. 1222. EXTENSION OF AUTHORITY TO PROVIDE ASSISTANCE TO COUNTER THE ISLAMIC STATE OF IRAQ AND THE LEVANT.

(a) In General.—Section 1236(a) of the Carl Levin and Howard P. “Buck” McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015 (Public Law 113–291; 128 Stat. 3559) is amended by striking “December 31, 2016” and inserting “December 31, 2019”.

(b) Additional Assessment On Certain Actions By Government Of Iraq.—Subsection (l)(1)(A) of such section, as added by section 1223(e) of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016 (Public Law 114–92. 129 Stat. 1050), is amended by striking “120 days after the date of the enactment of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2016” and inserting “each of March 25, 2016, and the date that is 120 days after the date of the enactment of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017”.

SEC. 1223. EXTENSION OF AUTHORITY TO SUPPORT OPERATIONS AND ACTIVITIES OF THE OFFICE OF SECURITY COOPERATION IN IRAQ.

(a) Extension.—Subsection (f)(1) of section 1215 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 (10 U.S.C. 113 note) is amended by striking “fiscal year 2016” and inserting “fiscal year 2017”.

(b) Amount Available.—Such section is further amended—

(1) in subsection (c), by striking “fiscal year 2016” and all that follows and inserting “fiscal year 2017 may not exceed $60,000,000”; and

(2) in subsection (d), by striking “fiscal year 2016” and inserting “fiscal year 2017”.

Michael Brenner’s confused critique

Someone named Michael Brenner has been circulating a lengthy critique of Power Wars, including distributing a version to his listserv [to which he unilaterally adds the e-mail addresses of people] on Thursday, uploading a version to Consortium News on Saturday, and uploading another version as a Huffington Post blog yesterday. It opens with a flattering thought – that my book is “much discussed” and is “destined to be a landmark in the writing of the period’s history.” But Brenner goes harshly critical from there, portraying the book as credulous and full of omissions, hinting that its alleged failings may have been bad faith on my part, and eventually abandoning the book to just express his negative views of the Obama administration as having institutionalized illegality in the war on terror.

I’ve been torn about whether to respond to Brenner for reasons – as will become clearer below – of compassion. On the one hand, his criticism is unnecessarily snide and personal, e.g. “Savage seems oblivious of this reality — or else, does a good job of pretending so.” On the other hand, his critique is so riddled with basic errors – like Gilda Ratner’s Saturday Night Live character Emily Latella, who would rant on the basis of a misunderstanding, then say “nevermind” – that I felt vicariously embarrassed for him. He seems to be a retired professor and has a page on the University of Pittsburgh website that lists various “papers,” although the most recent is from 2008 and several are just Microsoft Word files with little prose poems about political figures.

Unfortunately, Brenner keeps revising and circulating this essay to various places, and two people have now forwarded it to me. So I’m going to just point out a few of Brenner’s most egregious factual misunderstandings.

- Brenner keeps referring to this law, “The Patriot Act.” I do not think it means what he thinks it means.

He goes on and on for paragraphs about the Patriot Act (e.g., “The place of the Patriot Act in these lawyerly discourses is of central importance”) when the context shows that he is actually talking about the Authorization for Use of Military Force. Since the repeated mistake has stayed in as he has edited and re-edited versions of this, it was not a stray oversight. No one with a competent grasp of post-9/11 issues would make this mistake.

- Brenner somehow totally missed a lengthy discussion of the CIA-Senate Intelligence Committee fight in the book.

He spends three paragraphs about how “Savage’s lengthy account has another, more glaring omission. He makes no reference to the White House/CIA hacking of the Senate Intelligence Committee computers in Fall 2014 at the time of the standoff over release of the Committee’s report on rendition and torture. … Is this not arguably an impeachable offense? Why does Savage totally ignore it?”

Chapter 10, Section 13 is titled “The CIA versus the Intelligence Committee,” and it may be found on pages 512-515. The foundations for that fight are foreshadowed in Chapter 4, Section 6, “Seeds of the Senate Torture Report,” on pages 114-116, and in Chapter 8, Section 6, “Hair on Fire (Executive Privilege II)” on pages 432-435.

- Brenner complains that the book has no index, so it is “likely that most reviewers, therefore, have only a faint knowledge of its contents.”

The book has a 48-page index. As a page says in the spot where indexes go, after the endnotes, the full index is available online at charliesavage.com/powerwarsindex. This is also cited in the table of contents.

- Brenner misses many examples of the law mattering in the Obama era.

He maintains that “Savage can cite only two instances” of “where the White House did not do what it wanted to do – or where the President felt compelled to override a contrary interpretation by his lawyers in order to act as he was inclined.” One was the Libya War Powers Resolution episode and the other is the fight over whether Al Shabab in Somalia was targetable as a group.

Brenner seems not to have noticed the issue of failing to close Guantanamo due to Congressional transfer restrictions, a topic that consumes more pages of the book than any other. There’s also not bringing Dacduq out of Iraq. Not targeting al-Farekh. Starting to provide notice to criminal defendants when they faced evidence derived from FISA Amendments Act surveillance. Not granting deferred action to undocumented parents of DREAMers. That’s before you get to places where the law pushed them away from their initial inclinations prior to any final decision, like not bombing the bin Laden compound. Here’s a blog entry listing even more, derived from the book.

- Brenner writes that the Obama lawyers were just trying to come up with a baseball-like “in the vicinity” rule, except it was all secret memos and FISA court opinions the public had no access to, and that I seem “oblivious” of this reality.

Reflecting on the legitimacy of invoking merely “legally available” theories, especially where the law may be indeterminate or non-justiciable, and more broadly on whether the difference in lawyering between the Bush and Obama administration makes any difference in the end, is a central theme of the book. (See, e.g., pages 66-67, 151, 264, 647-648, 677-681, 687-688, 690-695).

The issue of “secret law” found in secret FISA court precedents and secret memos gets an entire chapter. (Chapter 9: “Secrecy and Secret Law,” found on pages 415-473.)

- “Context is the big missing ingredient in Savage’s 700 plus page opus. Fear and dread permeated the government as it did the country. President Obama’s one fixed reference point from the day he entered office was to avoid another traumatic act of terrorism that likely would make him a one-term President.”

The first and third chapter is all about this establishing this context, although I situate it as kicking in viscerally with the Christmas 2009 underwear bombing attack, rather than Inauguration Day.

I could go on, but I think the point is made.

Do the upstream v. Prism collection numbers from Judge Bates’ 2011 opinion add up?

Edit: Bottom line up front: Several widely cited numbers about the FISA Amendments Act warrantless surveillance program — that circa 2011 the NSA was collecting >250 million communications annually, of which 9 percent came from upstream and 91 percent came from Prism — may be inaccurate.

_________

On Medium, Beatrice Hanssen, a writer whom I have not encountered before, has published a lengthy and interesting essay taking a closer look at Judge John Bates’ October 2011 ruling about the FISA Amendments Act and upstream collection — the one about Multi-Communication Transactions (MCTs) which the government declassified in August 2013 after the Snowden leaks.

[Background: a MCT is when multiple messages are bundled together and transmitted over the Internet as a unit. If even one of them has a targeted selector, like the e-mail address of a foreign suspect, the NSA’s Upstream collection system will get a copy of all of them — even though the rest of the messages have nothing to do with the target.]

The Bates opinion, and coverage of it, focused on the issue of wholly domestic messages that got sucked in via MCTs – there were several thousand of them. But Hanssen argues that an element of this has been underappreciated: various figures in footnote 32 of the Bates opinion suggest that the NSA is taking in about 2.65 million MCTs a year. While most of them do not have wholly domestic messages, this is nevertheless a potentially huge amount of collection – depending in part on what the average number communications bundled together into a single MCT is, which we don’t know. She argues that this means upstream surveillance conducted under the FISA Amendments Act is bulkier than generally portrayed. She also complains that the judges who dismissed the two big legal challenges to upstream, Jewel and Wikimedia, have conflated the distinction between transactions and communications when citing the Bates opinion, obscuring the volume of messages the NSA is ingesting.

That seems right to me. Still, once you get away from the special legal problems raised by the warrantless collection of wholly domestic messages on domestic soil, it strikes me as a probably less voluminous parallel to the issues raised by Executive Order 12333-authorized bulk collection. (Indeed it is possible that many or most of the MCTs would be redundantly captured by both systems.) Both raise the question of how we think about the privacy rights of “innocent foreigners,” as she puts it, as well, I would add, about incidental collection of one-end-domestic communications.

Beyond that, though, in thinking about her essay, it also occurred to me that some widely cited numbers derived from Bates’ opinion in common circulation may be questionable. Specifically, Bates wrote that the NSA had told him that it collects “more than 250 million Internet communications” a year via the FISA Amendments Act, of which about 91 percent came from the Prism system and about 9 percent came from upstream. (Page 30-31)

Those figures have been echoed in a lot of places. Here they are in a Washington Post article, citing the opinion. The 250 million figure also shows up in the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board report about the FISA Amendments Act, also citing the opinion. And I cited them on page 217 of my book.

But is it possible that Bates was mixing apples and oranges? Or, rather, conflating “communications” – meaning discrete messages – with “transactions” – which, in MCT form, each contain many messages?

When we look closer at the total number of MCTs Hanssen draws our attention to, these figures start to look dubious. The footnote suggests that the NSA collects 26.5 million upstream transactions a year, of which 10 percent are MCTs, hence 2.65 million of those. If we assume that Bates was counting every transaction, singular or MCT, as one communication, the math kind of works: 26.5 million messages contributed by upstream is fairly close to 9 percent of >250 million total messages.

But once you think about the 2.65 million MCTs as each contributing multiple messages, the math starts to break down fast. When I asked ODNI a question about this during a briefing call with reporters when the ruling was released, the briefer used an example in which one MCT contained 15 discrete e-mails. That example, as Hanssen notes, would transform the 2.65 million MCTs into 39.75 million communications. Add in the other 23.85 million upstream transactions that were single messages, and upstream has contributed 63.6 million messages to the annual haul — in this hypothetical.

We don’t know what the right average multiplier is — 15 could be too high, but it could also be too low. Still, it sure looks reasonable to conclude that either there were significantly more than 250 million total communications collected annually under the FISA Amendments Act circa 2011, or that upstream’s contribution to the whole was significantly more than 9 percent. Or both.

How the FBI loosened limits on warrantless surveillance “backdoor searches” in 2011

At Just Security, Jake Laperruque writes about the recently declassified Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court opinion re-upping the FISA Amendments Act warrantless surveillance program for another year. That is the ruling in which Judge Hogan, after hearing constitutional concerns about backdoor searches by FBI agents working on ordinary criminal cases, reaffirmed that such searches are constitutional.

Jake is digging into other parts of the opinion and notes that Judge Hogan wrote that FBI agents may perform such a query even before opening an “assessment” — the bureau’s lowest level of criminal or national-security investigation. On Twitter, Jake and Marcy Wheeler were talking about this and I jumped in; Marcy says [update to emphasize: link is to a lengthy analysis she wrote about the same opinion on April 22; it also flagged the pre-assessment usage option] she is particularly concerned about language that says F.B.I. agents may do this not just to identify foreign intelligence or criminal information for their investigations or to decide whether to open an assessment, but for other, unspecified purposes (“are not limited to”).

I think something is knowable here that I want to explore in a greater than 140 characters. It doesn’t seem like “news,” but maybe will be interesting to specialists.

(Preliminary: Under the FISA Amendments Act, the government may collect, on domestic soil and without a warrant, messages of targeted non-citizens abroad – including when they communicate with Americans. A “backdoor search” is when government officials query the database of messages previously collected in that fashion using an American’s name or e-mail address as the search term. Some lawmakers want to require the government to get a warrant before using an American’s identifier as search term.)

Anyway, back in 2011, Valerie Caproni, then the FBI’s general counsel and now a Federal District Court judge in the Southern District of New York, revised the bureau’s Domestic Investigations and Operations Guide (basically, its manual of rules — agents call it the “DIOG”) in several ways that relaxed limits on agents’ powers. One was giving agents more leeway to search existing law enforcement databases without having to open an assessment first. From an article in June of that year about the forthcoming changes:

Some of the most notable changes apply to the lowest category of investigations, called an “assessment.” The category, created in December 2008, allows agents to look into people and organizations “proactively” and without firm evidence for suspecting criminal or terrorist activity.

Under current rules, agents must open such an inquiry before they can search for information about a person in a commercial or law enforcement database. Under the new rules, agents will be allowed to search such databases without making a record about their decision.

Mr. German said the change would make it harder to detect and deter inappropriate use of databases for personal purposes. But Ms. Caproni said it was too cumbersome to require agents to open formal inquiries before running quick checks. She also said agents could not put information uncovered from such searches into F.B.I. files unless they later opened an assessment.

I haven’t thought about that article for a long time, but this Twitter exchange reminded me of it. The FBI completed the new manual in October 2011 and later released a redacted version of it, so we can see what this change regarding searches of databases looked like. In post-Snowden hindsight, relaxing limits on queries of FISA Amendments Act data was clearly a part of it. Specifically, the manual had a new section for “Activities Authorized Prior to Opening An Assessment,” which indeed includes permitting searches of law enforcement “records or information.”

If we turn to Section 18.5.2, we see what “records or information” means in greater detail. It means performing a probably federated query across all law enforcement databases, explicitly including “raw FISA collections.”

The discussion about restricted access to certain records may at first glance seem like agents do not get to query raw FISA collections, but “access” is is instead about needing permission to read any “hits” returned from a query. An endnote in Power Wars explains how this works ** :

So. We know the FBI first gained access to its own repository of the raw fruits of FISA Amendments Act surveillance in October 2009, when the intelligence court permitted it to begin keeping its own copy of certain Prism system data to process for its own ends, rather than just serving as a conduit for it to flow from webmail companies to the NSA.* (The NSA doesn’t share with the bureau raw access to the other two types of FISA Amendments Act data – upstream Internet and international phone calls.) At that point, agents could perform “backdoor” queries for open assessments and preliminary and full investigations.

Now we can see more clearly that in October 2011, the FBI granted agents greater leeway to search through that information — even when they were not actively investigating anything, but rather whenever they are “initially processing a complaint, observation, or information.” Whatever that means.

On the other hand, Judge Hogan’s opinion also highlighted this section of the PCLOB report on the FISA Amendments Act (from two GOP members of the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board’s separate statement). It suggests that in practice, this may all be much ado about nothing when it comes to backdoor searches for criminal-case purposes, as opposed to national-security investigations:

Judge Hogan ordered the Justice Department to begin reporting to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court every time agents working on non-security investigations read Americans’ private messages following a backdoor search. Perhaps the Office of the Director of National Intelligence will be kind enough to declassify redacted versions of any such filings or a future court opinion summarizing them, so the rest of us can know, too.

—

* As Judge Hogan pointed out, the FBI doesn’t get all raw Prism data, just collection from tasked selectors that are deemed relevant to one of its open investigations. That would presumably include anything related to terrorism, since it has open-ended “enterprise” investigations into groups like Al Qaeda, but perhaps not intelligence collection related to more run-of-the-mill diplomatic espionage.

** [EDIT TO ADD THIS]

It’s worth including that Judge Hogan discusses this process in his ruling. The context is that the FBI included new language in the minimization rules this round saying that queries that do not return direct access to FISA Amendments Act intercepts will not count as a “query,” even if they do return a notification of a “hit.” Judge Hogan was fine with that, and styled this description as a clarification rather than a change:

The government has added language to the querying provisions of the FBI Minimization Procedures to clarify that a search of an FBI storage system containing acquired information does not constitute a “query” within the meaning of the procedures if the user conducting the search does not receive access to unminimized Section 702-acquired information in response to the search. In such cases, the query results include a notification that the queried dataset contains Section 702-acquired information responsive to the query.

The new language also clarifies what actions an agent or analyst without appropriate training and access to Section 702 information may take upon receiving a positive “hit” indicating the existence of (but not access to) responsive information. Such a user may request that FBI personnel with Section 702 access rerun the query if it otherwise would be authorized by the FBI Minimization Procedures and if the request is approved by both the user’s supervisor and by a national security supervisor. Generally speaking, the user without access to FISA-acquired information can be provided with access to information contained in the query results only if such information reasonably appears (based on the review of FBI personnel with authorized access to Section 702-acquired information) to be foreign intelligence information, to be necessary to understand foreign intelligence information, or to be evidence of a crime. If it is “unclear,” however, whether one of these standards is met, “the user, who does not otherwise have authorized access may review the query result solely in order to assist in the determination of whether information contained within the results meets those standards.” According to the government, such situations are “very rare.”

(From pages 28-29; citations and footnotes omitted.)

Zazi got a super-belated warrantless surveillance notice while no one was looking

After the Snowden leaks, government surveillance defenders’ best and most often-cited example about the value of post-9/11 electronic spying programs was the discovery of Najibullah Zazi in 2009, just days before an intended bombing of the New York City subway. Zazi, who had trained with Al Qaeda in Pakistan, had made the mistake of sending an email to a Qaeda-associated e-mail account that the government had targeted for warrantless surveillance under the FISA Amendments Act, and the plot was foiled.

Another thing that happened after the Snowden leaks was that it came to wider light that national security prosecutors had been concealing from defendants the fact that they faced evidence derived from FISA Amendments Act surveillance. As a result, no one knew he had standing to challenge the constitutionality of that law. Solicitor General Donald Verrilli, who had told the Supreme Court that the Justice Department had a legal obligation to notify defendants when they faced such surveillance, forced through a change in that practice, and the Justice Department began notifying a handful of defendants. See Power Wars chapter 11 (Institutionalized: Surveillance 2009-2015), section 8 (Evidence Derived from Warrantless Surveillance).

But it never notified Zazi, which was puzzling. When the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board issued its big report on the program in July 2014, Marcy Wheeler observed on Emptywheel that it had seemingly overlooked some examples of defendants who looked like maybe they should have received notice but had not. Zazi was the clearest cut example of these, given how much the government was openly saying that FISA Amendments Act surveillance had specifically prompted the investigation into him.

In writing an article published tonight about several recent notices to defendants, I learned that the government, when no one was paying attention, had super-belatedly notified Zazi in July 2015. It was no secret that his email had been incidentally intercepted under that program, so this isn’t exactly news – especially since he’s not challenging it. But there it is.

Bonus: Another little-noticed notice, if you will, was in a case arising in the Northern District of Ohio – notices went out last December. When I reconstructed the meeting at which Deputy Attorney General Jim Cole decided to start notifying defendants for that section of Power Wars, I learned that the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Ohio, Steven Dettelbach, was one of the federal prosecutors who called into the meeting. That was mysterious at the time; there was an obvious reason why every other U.S. attorney participating in the meeting had a reason to be there. Knowing this case was in the works makes it make sense that Dettelbach was invited to weigh in, too.

Here’s the Zazi notice:

USA Freedom Act coalition vets fire warning shot, demand more information about Americans’ e-mails swept in by warrantless surveillance program

I end the second chapter on the once-hidden history of surveillance 1978-2015 in Power Wars with a behind-the-scenes reconstruction of the fight to enact the USA Freedom Act and then a forward-looking focus on the “backdoor search” loophole, whereby government agents search private communications by Americans that the NSA gathered “incidentally” and without a warrant:

[T]he Freedom Act fight had demonstrated that a bipartisan House majority, combined with a “sunset” deadline that risked letting the entire law expire if no bill at all passed, could overcome resistance. The FISA Amendments Act was set to expire on December 17, 2017. …

Congress may yet impose further checks and balances on when government agents may search surveillance databases for incidentally collected private communications of Americans — regardless of which legal authority the government used to collect them. But as Obama’s time in power neared its end, there was little sign that he would be the president who ushered in that change.

That fight began to take shape today when 13 members of the House Judiciary Committee from both parties sent a bipartisan letter to James Clapper, the director of national intelligence, asking him to answer what has been one of the most significant open questions about the National Security Agency’s warrantless surveillance program: how many private messages of Americans it sweeps up under the FISA Amendments Act.

The government has been reluctant to provide that information, saying it is too difficult to come up with a reliable estimate. But with the FISA Amendments Act — also known as Section 702 — expiration coming, the lawmakers made clear that they think they have leverage to force the executive branch to be more forthcoming.

In the House of Representatives, it will fall first to our Committee to determine whether Congress should extend Section 702 beyond its scheduled sunset on December 31, 2017. You have willingly shared information with us about the important and actionable intelligence obtained under these surveillance programs. Now we require your assistance in making a determination that the privacy protections in place are functioning as designed.

Eight Democrats signed the letter, including Rep. John Conyers of Michigan, the ranking member of the Judiciary Committee. Six Republicans did, including Rep. James Sensenbrenner of Wisconsin, a former chairman of the committee who played a major role in the enactment last June of the USA Freedom Act, ending the NSA’s bulk collection of domestic calling records under a secret interpretation of the Patriot Act.

The Bush administration started both the warrantless surveillance and bulk data collection programs as part of its then-secret Stellarwind program after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. In 2008, Congress legalized a form of the warrantless surveillance program by enacting the FISA Amendments Act. It permits the government, on domestic soil, to collect international e-mails and phone calls of non-citizens abroad – even when its targets communicate with Americans.

Some people don’t want this program to keep going at all; the A.C.L.U. has been a big critic, in court and in debate. But it doesn’t seem particularly realistic that majorities exist in Congress who will want to roll it back. However, there is also dispute over what rules should apply to private messages of Americans when the program has “incidentally” collected them. Earlier this week, the government declassified a ruling by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court concluding that it is constitutional for F.B.I. agents, working on criminal cases, to search for Americans’ names and e-mail addresses in the program’s repository.

Some lawmakers want to require the F.B.I. to get a warrant before conducting such a search, and the House has twice voted for amendments to do that, only to have leadership drop the amendment in conference with the Senate. But the public debate over that proposal has been impaired by a lack of information about how many American messages the government is collecting without a warrant. (The N.S.A. also incidentally collects Americans’ communications when the agency is operating abroad under Executive Order 12333 and is permitted to vacuum up content in bulk without targeting anyone; the volume of that collection is also unknown. Members of Congress so far don’t seem particularly aware of this wrinkle.)

The letter is not the first time the Obama administration has been asked to shed light on the scale of incidental collection. For years, Senator Ron Wyden, Democrat of Oregon, has asked for data on the question. And in 2014, the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, an independent watchdog agency, recommended in a report about the warrantless surveillance program that the government annually say how many phone calls and e-mails involving Americans it has intercepted.

But the government has declined, arguing that it would be too difficult and resource-intensive to come up with an exact count. In a February 2016 follow-up report, the privacy board said that the N.S.A. had “considered various approaches” to carrying out its recommendation, it had also “confronted a variety of challenges” to doing so.

Still, the letter sent by the lawmakers on Friday pointed out that the N.S.A. has already shown that it can study a sampling of raw intercepts to get a “rough estimate” of what is in them because it did so in 2011 in response to a problem that arose before the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court.

“We acknowledge that this estimate will be an imperfect substitute for a more precise accounting—but surely the American public is entitled to some idea of how many of our communications are swept up by these programs,” they wrote.

[Updated with video, verbatim Q&A] Brian Egan’s ASIL speech and questions about rules for drone strikes in tribal Pakistan and for assessing collateral damage

Yesterday, Brian Egan, the Obama administration’s recently confirmed State Department legal adviser (and former National Security Council legal adviser), gave a speech at the annual American Society of International Law conference about “International Law, Legal Diplomacy, and the Counter-ISIL Campaign.” Egan’s speech was an excellent distillation of the Obama administration’s argument for why it thinks everything it has been doing in counterterrorism strikes, against the Islamic State and otherwise, has complied with international law – something that some scholars dispute when it comes to certain novel questions about imminence, sovereignty, and other issues. (Marty Lederman has a good write-up summarizing its key points at Just Security.) I happened to be sitting near the microphone, so asked him two quick questions during Q&A — one seeking clarity about the status of tribal Pakistan for battlefield targeting rules, and one seeking clarity about how the government makes collateral damage assessments. This post explains the issues, and why one of his answers was clear but the other was not. I can’t find video of the speech posted anywhere, but I’ve embedded some Tweets.

Update: Here is the video; our exchange starts just after the 43 minute mark.

State Legal Advisor Brian Egan addressing #ASILAnnual pic.twitter.com/1z0irH01xo

— Heather Brandon (@HeatherEBrandon) April 1, 2016

Brian Egan just said he’s going to take questions!! #ASILAnnual

— Heather Brandon (@HeatherEBrandon) April 1, 2016

First up: @charlie_savage #ASILAnnual pic.twitter.com/EjFsO8pPhQ

— Heather Brandon (@HeatherEBrandon) April 1, 2016

Thanks to @charlie_savage for his question at #ASILAnnual to @StateDept Legal Adviser Brian Egan.

— ASIL (@asilorg) April 1, 2016

QUESTION ONE: IS TRIBAL PAKISTAN A HOT BATTLEFIELD WHERE THE PPG DOES NOT APPLY?

In one part of his speech, Egan talked about the May 2013 Presidential Policy Guidance (PPG), which imposed tighter standards on counterterrorism strikes away from hot battlefields, like like requiring near certainty that there will be no civilian casualties – a higher limit than international law requires under the law of armed conflict or self defense. Egan noted that this does not apply in places where there is a zone of active armed conflict:

The phrase “areas of active hostilities” is not a legal term of art—it is a term specific to the PPG. For the purpose of the PPG, the determination that a region is an “area of active hostilities” takes into account, among other things, the scope and intensity of the fighting. The Administration currently considers Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria to be “areas of active hostilities,” which means that the PPG does not apply to operations in those States.

It has long been my understanding that the PPG did not apply to tribal Pakistan – the FATA region along the border with Afghanistan, which the Pakistani government does not really control. That’s important because the overwhelming majority of CIA drone strikes have taken place there, including its campaign, since 2008, of “signature” strikes aimed at groups of men who look like militants but whose identities are not known, raising the risk of civilian deaths. The purpose for that campaign is not just to take out high level Al Qaeda leaders, but also run-of-the-mill insurgents who stage attacks on U.S. troops across the border in Afghanistan.

So I asked Egan whether he could clarify if tribal Pakistan counted as an extension of Afghanistan, where the PPG does not apply, or as a separate place that is not an area of active hostilities, where the PPG does apply?

Egan clearly indicated that the border region, on the Pakistani side, was still part of the battlefield, so PPG limits did not apply there.

Egan: Pakistan border region part of zone of active hostilities. #ASILAnnual

— Heather Brandon (@HeatherEBrandon) April 1, 2016Update:

Update: Now that the video is available, here is the exact exchange:

Q) One, on your clarification of the ‘zone of active hostilities’ and where the PPG does and does not apply, does tribal Pakistan count as an extension of Afghanistan for the purpose of the PPG not applying, or does it count as a ‘not hot battlefield’ where the PPG does apply?

A) With respect to the first, the question of ‘area of active hostilities,’ when I mentioned Afghanistan, I think sometimes others have referred to the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region as being part of what we talk about with respect to ‘Afghanistan.’

QUESTION TWO: WHAT CRITERIA DOES THE U.S. USE WHEN ASSESSING WHETHER THERE WAS ANY COLLATERAL DAMAGE AFTER A STRIKE?

In another part of his speech, Egan talked in some detail about the various factors the government uses to decide whether a potential target would be a lawful object of attack, as opposed to a civilian who is not taking part in hostilities. Along the way, he made the comment I’ve bolded here so you can see it in context:

In many cases we are dealing with an enemy who does not wear uniforms or otherwise seek to distinguish itself from the civilian population. In these circumstances, we look to all available real-time and historical information to determine whether a potential target would be a lawful object of attack. To emphasize a point that we have made previously, it is not the case that all adult males in the vicinity of a target are deemed combatants. Among other things, the United States may consider certain operational activities, characteristics, and identifiers when determining whether an individual is taking a direct part in hostilities or whether the individual may formally or functionally be considered a member of an organized armed group with which we are engaged in an armed conflict. For example, with respect to membership in an organized armed group, we may examine the extent to which the individual performs functions for the benefit of the group that are analogous to those traditionally performed by members of State militaries that are liable to attack; is carrying out or giving orders to others within the group to perform such functions; or has undertaken certain acts that reliably indicate meaningful integration into the group.

This is a reference to controversy over an assertion first reported by my colleagues Scott Shane and Jo Becker in a deeply reported 2012 article they wrote in the New York Times about Obama and drone strikes:

…Mr. Obama embraced a disputed method for counting civilian casualties that did little to box him in. It in effect counts all military-age males in a strike zone as combatants, according to several administration officials, unless there is explicit intelligence posthumously proving them innocent. …

This counting method may partly explain the official claims of extraordinarily low collateral deaths. … The C.I.A. accounting has so troubled some administration officials outside the agency that they have brought their concerns to the White House. One called it “guilt by association” that has led to “deceptive” estimates of civilian casualties.

“It bothers me when they say there were seven guys, so they must all be militants,” the official said. “They count the corpses and they’re not really sure who they are.”

After that article came out, various administration officials pushed back, saying that this part was simply wrong. But last October, when The Intercept published some leaked documents about JSOC drone strikes (so they involved the military, not the C.I.A.), one of the most important details seemed to dovetail with it. The document was a presentation about a 13-month campaign in northeastern Afghanistan from 2012 to 2013 called Operation Haymaker. There had been 56 kinetic strikes, killing 35 targets (“JP,” in the slidedeck, short for”jackpots,” lingo for a specifically intended target) and 219 other people. All 219 other people killed because they were in the strike zone were deemed to have been combatants (“EKIA,” meaning enemies killed in action). None of the 219 were deemed civilian casualties/collateral damage or deemed to be status unknown.

While Egan’s speech seemed to frame the issue as being about ex ante decisionmaking — if we can target X, may we also target that other guy Y because he is an adult male nearby? — I had understood the issue to be more about after-the-fact assessments. I pointed that out as well as the leaked drone strike data, and asked Egan if it were not the case that all dead adult males in the vicinity of a target are presumed to have been combatants in the absence of additional information about who they were, then how do collateral damage assessments work instead?

@charlie_savage from @nytimes asks Egan @StateDept clarification on how state defines combatents & collateral damage https://t.co/zf5xLOTpDq

— Patricia G. Ferreira (@Pat_Galvao) April 1, 2016

A lot of people would really like to know the answer to that.

Wow. Great q for Brian Egan at #ASILAnnual came from Charlie Savage @nytimes about calculations of “collateral damage”

— bechamilton (@bechamilton) April 1, 2016

Egan reiterated that the government did not simply presume that any adult male near a target in a strike zone to be a combatant, instead taking many factors into play.

Egan: Military age males NOT automatically considered combatants. #ASILAnnual

— Heather Brandon (@HeatherEBrandon) April 1, 2016

But he didn’t specify what those factors are. We can guess at some obvious ones – for example, did the drone, looking down at the site, see the mystery guy holding a weapon? did he seem to be following the target’s orders? But the core of issue, which remains unknown, is what the default presumption is when there is no information other than that there is an extra dead man down there, identity unknown. So his answer to that one — probably through no fault of his own, since a lot of this stuff is classified and it was a public setting — was not really satisfying.

Update: Here is the verbatim exchange from the video:

Q) And secondly, on the military-aged males thing. Now I haven’t written about that but my colleagues at the Times first wrote about that in 2012, and I immediately began hearing push-back from people in positions not unlike you’ve held in recent years that that wasn’t correct. But then it seemed to have been confirmed in the leaked drone papers published by the Intercept. And my understanding is it’s less about well if someone if someone is a military-aged male near a target then they are themselves a valid target, an ex ante calculation, but it’s more about after the fact, how do we calculate collateral damage? If it’s the case that some military-age males are dead near the strike zone and that is all that is know about them, are they counted as ‘collateral damage’ by virtue of that, or are they counted as ‘enemies killed in action’ by virtue of that? And I would note that the drone papers showed that in 13 month period of JSOC targeting, there were 35 targets killed and 219 bystanders killed as part of those targeting and all 219 were categorized as enemies killed in action.

A) Secondly on the issue of military-age males. It is not the case that a military-age male is considered a combatant solely by virtue of his being a military-age male. And I think that would apply both to assessments prior to a strike and assessments taken, after-action reports after a strike. So there are a variety of factors that are looked at in both cases. But it’s not that one’s military-age male status on its own would suffice.

Thanks @charlie_savage for asking Brian Egan about US collateral damage assessments. Unfortunately we still don’t know what the answer is…

— Shiri Krebs (@ShiriKrebs) April 2, 2016